In today’s post:

Q (not) A Beauty & Pop Culture Questions

The Full Beat Behind the Hair: The 1970s Synthetic Hair Revolution

How incredibly brilliant was the decision to cast Pamela Anderson as the star of Showgirl? Anderson plays a woman who is struggling to navigate life after her career as a Las Vegas showgirl ends abruptly after 30 years. It is exceptionally cool that Anderson, a longtime symbol of beauty, is working on a film that mirrors the issues an aging actress in Hollywood might face.

Did you read the Vogue piece on the significance of pink and green at the DNC? Hannah Jackson talks about the significance of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated in Vice-President Kamala Harris’ personal and political life. As a proud member I was thrilled to see our colors highlighted in Vogue.

Who knew that Venus “The G.O.A.T” Williams is also a major patron of visual artists? Williams is collaborating with the Carnegie Museum of Art on a podcast series about the relationship between photography and the environment. In her interview with Alayo Akinkugbe Williams talks about how marginalization in the arts and sports speaks to her interest in both fields.

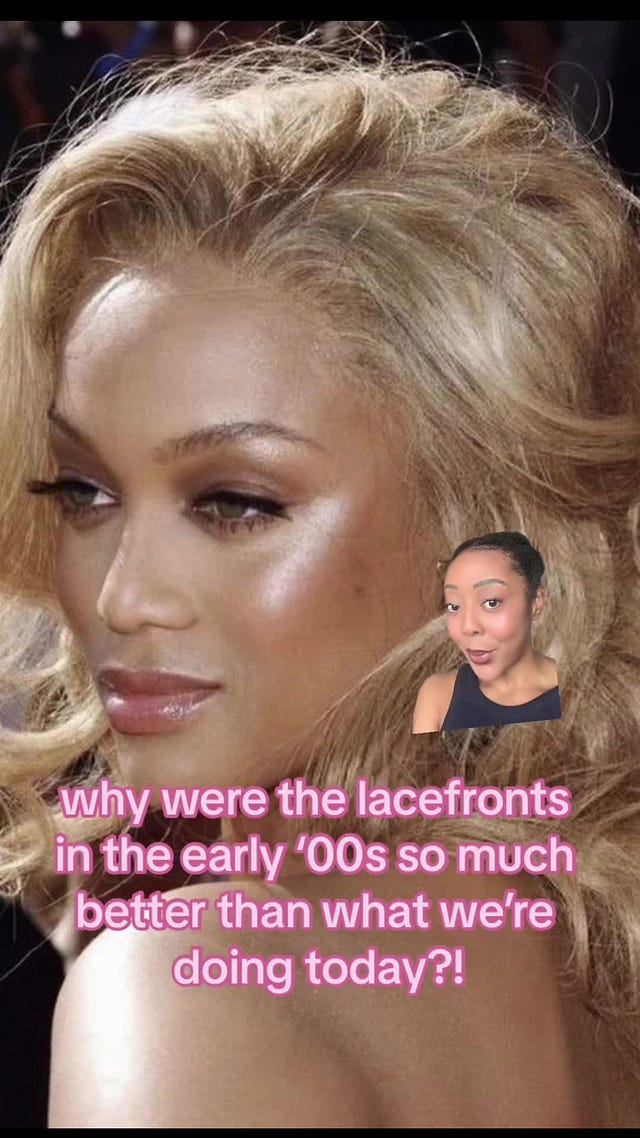

Synthetic, human hair, HD lace, and U Part units are only a few of the types of wigs available today. Any of these units can be purchased from a local beauty supply store, Amazon, or be customized by specialists on social media. The variety and quality of wigs that are available today are markedly different from 10-20 years ago. The earliest iterations of lace wigs debuted on mega celebrities like Beyoncé, Tyra Banks, and Mary J. Blige. These stars had access to master stylists like Kim Kimble, who may have been creating these units with $10,000 budgets.

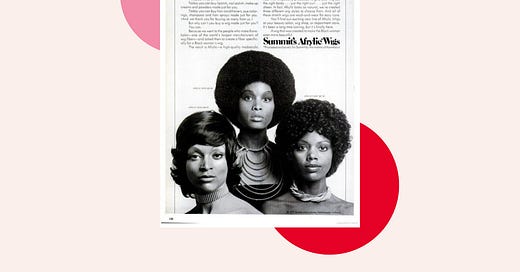

But before these large budgets and human hair innovations were readily available, what were Black women’s synthetic wig options like? Synthetic wigs and weaves have been a staple in Black women's beauty routines for at least half a century. I collect Black women’s lifestyle magazines from the early 2000s, but occasionally open my collection to older issues of Ebony magazines. Some of the most gorgeous ads are for synthetic wigs and pieces. Images like the following reflect Black women's interest in synthetic wigs as easy to manage and affordable hairstyling options.

While this image is from the 1970s, we know that Black women were also wearing synthetic hair in the 1950s-1960s, especially to achieve the popular bouffant style. Aimee Simeon writes that until the 1950s, most wigs were primarily made by hand but machines developed in Hong Kong mass-produced hairpieces, making them more accessible and affordable. This allowed the public to mimic the hairstyles of popular girl groups like The Supremes or The Ronettes with ease.

In an interview about wigs and hair loss, historian Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka says, wigs were part of performances. “With all the variations of Black hair, these wigs were used to create hair uniformity. There was a theatrical element. Even if we look at some of the movies from the 1970s, we knew that they were wearing afro wigs." There is a noticeable difference between the wigs popularized by midcentury Doo Wop starlets and those with kinkier textures.

Wig development continued in Hong Kong on the production and texture fronts through the 1960s. An Encyclopedia entry on wigs notes an “invention of the machine-made, washable, nylon and acrylic wig in Hong Kong led to cheap, mass-produced wigs flooding the market.” The entry goes on to claim that in 1969 about 40% of wigs were synthetic and being produced by “the American firm Dynel and the Japanese Kaneka [Kanekalon sellers], who both used modacrylics to create wigs that were easy to care for and held curl well.” Synthetic wigs, also called novelty fashion wigs, became one of Hong Kong's fastest growing exports by 1970.

Watch this commercial for Supreme Wigs, promoted by The Supremes in the 1970s.

Kankelon’s similarity to some Black hair textures is another important reason for the explosion in synthetic wigs. Brooklyn White, culture writer, argues that although kankelon “isn’t exclusive to our culture, most assumed it’s a Black innovation because we invest in it the most. Even if we aren’t responsible for its creation, its legacy started with our demand for it.” White also notes that although its specific origins are unclear and that the development of mainstream kankelon hair was the result of a trickle up effect from Korean beauty supply store owners to media and beauty industries, to manufacturers. This is an interesting divergence from the argument that Chinese manufacturers introduced the products with “varied” textures to customers.

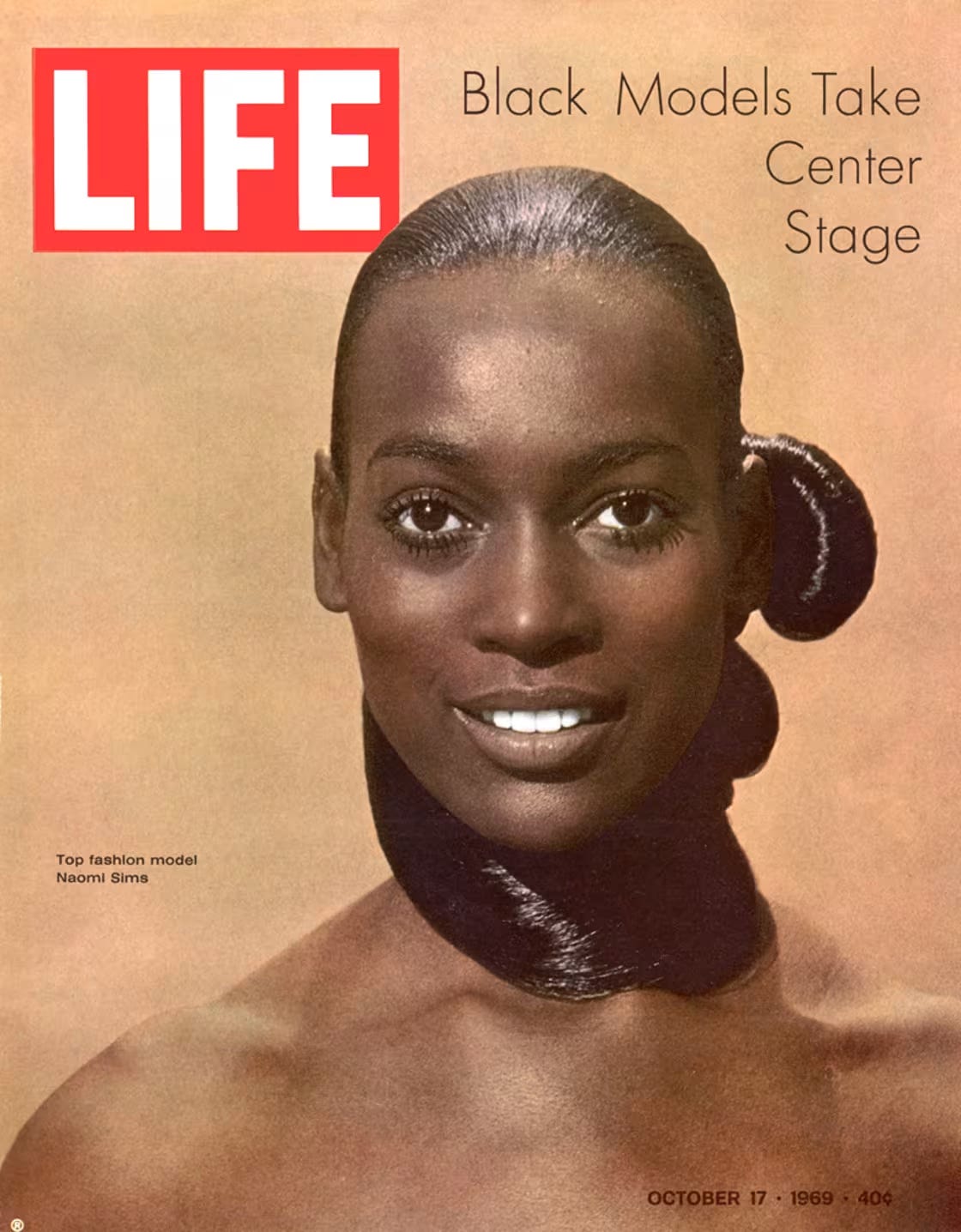

Most important though, is that supermodel Naomi Sims, was inspired by her experience doing her own hair before shows and shoots to create her own wig line. She decided to launch the Naomi Sims Collection of wigs, after learning that “Black women represented about 40 percent of the wig-purchasing market.” In her now famous interview with Carol Krucoff, Sims laments that despite our financial investments in wigs, Black women were not part of the decision making processes in development or production. In response she created Kanekalon Presselle, which catered to Black women by developing textures that were more accurate to Black hair textures than Kankelon’s initial iterations or Dynel.

Click here to see which global superstar channeled Naomi Sims in her magazine cover.

Later in her interview with Carol Krucoff, Sims comments on appropriation, "Whatever the well-dressed young child or black man in Harlem is wearing is immediately seized by the fashion industry, but they are never given credit. I've always worn black designers' clothes and white designers have copied them." This is an ironic observation considering that Sims is not heralded for her impact on wig development and production as much as she should be.

I am obsessed with the minutiae of Black women's beauty culture. Questions like who was mass producing these wigs? Were any Black on staff to determine which styles should be created? How were they blending the hair with their natural curls since the units were typcially partless? Information about our hair, hair stylists, and techniques to blend and/or protect their hair underneath is scarce or difficult to corroboate against other sources. In my search for this and similar information I came across very few direct sources, that were both freely accessible and reputable, to learn more. Brooklyn White’s piece on Sims pioneering wig line was truly a breath of fresh air. This lack of serious and detailed investigation into Black women’s hairstyling practices, is a frustrating and common occurrence in my search to learn about Black women’s beauty culture and practices.