This Black History Month BlackBeautyPop is doing a series on the relationship between relaxers and Black women’s health. Chemical relaxers have been in and out of the news because of (1) concerns about their impact on our health and (2) the growing legal responses to these alleged harms. Each week I will cover the historical, scientific, and legal context of Black women’s relationship with relaxers in the U.S.

Because this piece is so much longer than the other BlackBeautyPop pieces, I recorded an audible version for my short attention span beauties.

[00:00] Intro

[00:41] 1900 - 1930

[02:11] 1930 - 1960

[03:52] 1960 - 1980

[06:55] 1980 - 2000

[08:26] 2000 - 2020s

[10:00] Conclusion/Part Two Preview

1900 - 1930

According to various outlets, Garrett A. Morgan invented a chemical hair straightener (the earliest iteration of the relaxer) accidentally in 1909. However, this information is not easily verifiable in credible and publicly accessible sources. While Morgan was trying to develop a chemical solution to a sewing machine issue he noticed that the mixture straightened the fabric it came into contact with. Morgan tested the mixture by applying it to a neighboring dog’s fur and then to his hair. Morgan reformulated the cream and sold it through his company, G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Company, which ads reveal was established in 1905.

During this period Black Americans were painstakingly integrating themselves into higher socio-economic classes. Historians argue that one attempt at social “elevation” was to use one’s appearance to contest racist depictions of Black Americans in all manner of media. Unfortunately, much of the desire to integrate engendered a colorist and texturist beauty standard that was upheld intraracially. Specifically, preferential treatment of lighter-skinned Black Americans, with light eyes and hair with looser curl patterns, which we can still recognize today. Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharps write that although early Black cosmetic entrepreneurs did not encourage their customers to defy beauty standards, it is absurd to point to them as having orchestrated colorism or texturism. Much like today, there was significant resistance to hair straightening tools and products from other Black people even in the early 20th century.

1930 - 1960

The 1933 ad for Morgan’s straightening product includes a testimonial from Duke Ellington, “The Jazz King.” This is important because many forget that early customers for chemical hair straighteners were primarily Black men. At this time Black women were using the press and curl technique, popularized by Madam C.J. Walker, which required the use of hot combs. Black women were also early consumers of hair pieces often called falsies. Black men on the other hand were experimenting with chemical straighteners to develop one that got hair straighter and lasted longer.

In barbershops across the nation men were using a caustic solution of potatoes, eggs, and lye, a semi-permanent straightener called a process, conk, or congalene. In the famous scene from Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, the seemingly unbearable mixture almost immediately burns X’s scalp. In the background viewers watch Shorty add chopped potatoes and eggs to the “Red Devil” lye mixture. According to Maxine Craig “Wearing a conk, one could be like the entertainers, who were virtually the only African Americans who received national recognition. To others it bore the stigma (or appeal) of its association with dangerous men.”

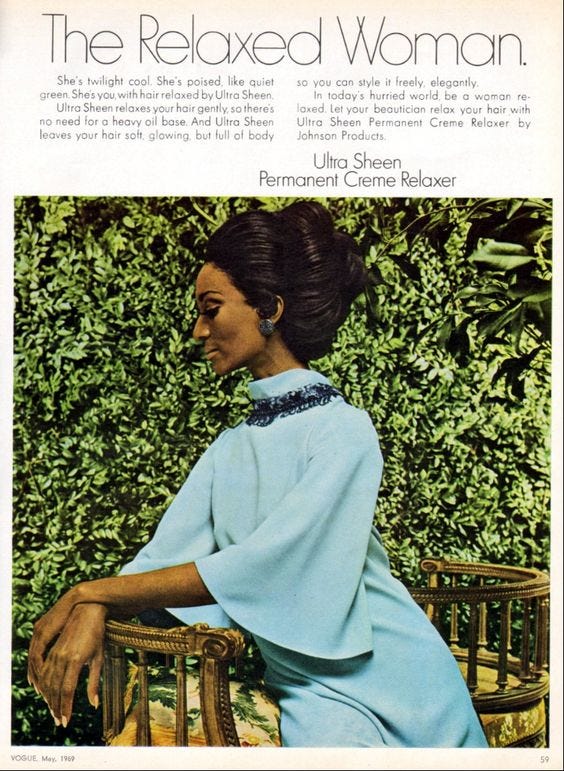

By the late 1940s chemical relaxers were transitioning out of the barber shops and being marketed to Black women for use at home. Black-owned companies like Johnson Products entered the cosmetic market and were quickly rewarded for their innovation. Atiya Jordan writes, “The company’s first product was the Ultra Wave, a hair relaxer for men. Then came Ultra Sheen, a hair straightener for women that offered a DIY process in the comfort of one’s home instead of spending uncomfortable hours at a hair salon.” Other companies, many white-owned, wanted a piece of the profit and developed similar lye-based chemical relaxers for at-home use.

1960-1980

As X came into consciousness about the power and beauty of Blackness, he argued that wearing one’s hair process represented a privileging of white beauty standards. Malcolm X’s gradual condemnation of hair processing reflects the uneasy split many felt about chemical straighteners as the nation entered its Black is Beautiful era. The Black is Beautiful era refers to the celebration of Black culture, identity, and hair. Per the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) “The movement affirmed natural hairstyles like the “Afro” and the variety of skin colors, hair textures, and physical characteristics found in the African American community.” As Black youth began seeking liberation in every area of their lives their hair became a living testament to their politics. In their appearance, young people rejected chemical straighteners and tools in favor of sky-high afros and naturals.1 This does not mean that the Black cosmetic industry came to a screeching halt. As the period illuminated the beauty of Blackness, it also revealed the depths of generational differences. Much of the Black is Beautiful era and the embrace of the afro was led by the youth. At the same time, their older family members remained committed to straightening their hair with chemical relaxers and hot tools.

In 1965 the Johnson Products company produced the Ultra Sheen No-Base hair relaxer, which was the first to include a cream that shielded the scalp against burning. The Johnson couple did not wait the advised two years for product testing but instead went direct to consumers that same year. The product was a huge success and the direct-to-consumer lye-based relaxer was copied by white-owned companies. Not only did they develop chemical relaxers, but they also targeted the same audience, Black women. By 1970 these cosmetic companies were working to mark afros as unmanageable, in comparison to straight hair. Companies like Clairol relied on African American vernacular which some argue “trivialized and diminished the political significance of the Afro itself.” These tactics did not easily thwart Black-owned companies like Johnson Products, who still controlled 60% of the Black hair care market. However, the intervention of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) cemented white-owned companies’ lead in the chemical relaxer department. In 1975 The FTC ordered Johnson Products’ Ultra Sheen relaxer to add a warning label to its boxes because they contained lye. Earlier, I mentioned that other companies had copied Ultra Sheen’s formula, which included lye. Even though all relaxers at the time contained it, no other companies were required to add warning labels to their products for nearly two years. Companies, especially Revlon, used the warning on Ultra Sheen to promote their relaxers as safer for consumers.

In 1978 Dark & Lovely made one of the biggest innovations in relaxers until that point, by developing the no-lye relaxer. According to Erica Culpepper, general manager of multicultural beauty at L'Oréal, "It was a huge technological breakthrough because, at the time, there were only lye relaxers on the market, which were much more damaging to consumers' hair.” The convenience of at-home no-lye relaxers aligned with the de-politicization of natural hair, and by the end of the 1970s relaxer sales regained momentum.

1980 - 2000

The 1980s ushered in a shift towards maximalist style and beauty. The Fashion Institute of Technology says of the period, ostentatious glamour and self-confident fashion were manifested in a variety of extravagant styles. Hip-hop, now about a decade old, experienced heightened coverage and further extended its influence. With increased exposure on shows like Video Music Box (1983) and Yo! MTV Raps (1984) rappers’ big hair, logo-embossed clothing, and huge chains revealed a convergence of luxury and maximalism that was unparalleled.

Popular hairstyles among Black women were haircuts that were cut asymmetrically and stacked all over. Many of these styles included a straight base and thus required the wearer to have a relaxer. In a 2016 interview, stacked style pioneer, Pepa (of Salt-N-Pepa) revealed that her hairstyle was the result of a relaxer burning off some of her hair. Not unlike the original hair straightening products, men were major cosmetic consumers. For many Black men, the Jheri Curl, or curly perm, dominated as the premier chemically altered style. This style had a co-sign from one of the biggest celebrities in the world, Michael Jackson.

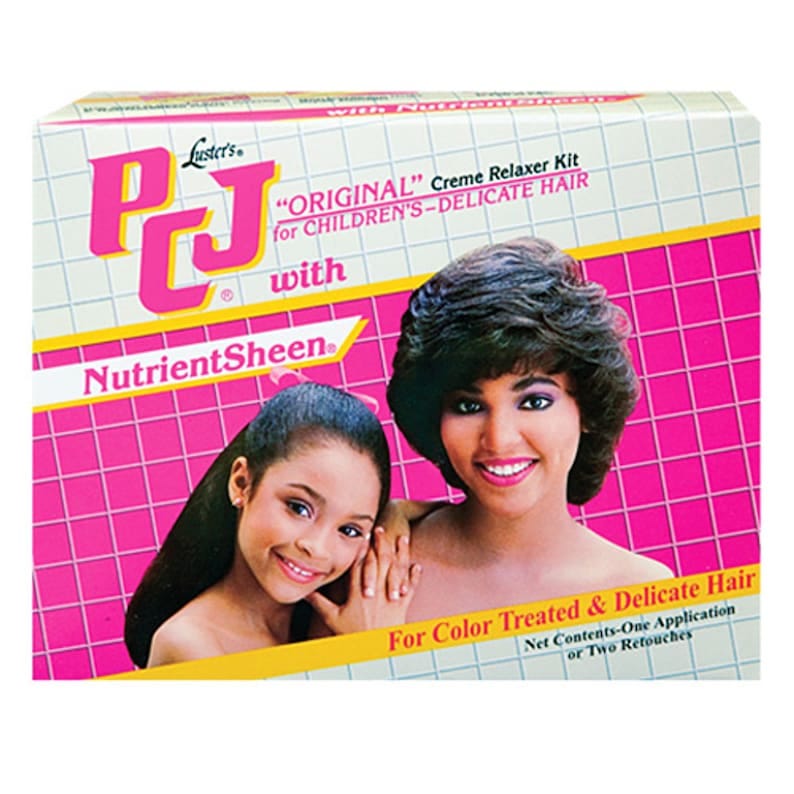

By the 1990s corporations expanded their interests to Black girls and developed brands like Just for Me. Marketed as “gentler” than those already on shelves, this was a major marketing innovation. Kiddie perms have not proven different from “adult” no-lye perms which had been on the market for decades. Recently, it was revealed that many of the girls on the boxes had never even been relaxed. Many of the styles that we thought a relaxer would help us achieve, were the result of a good old press and curl.

2000 - 2020s

In a mid-2000s interview, Howard B. Bernick, President and CEO of Alberto-Culver boasted “The African-American market is growing in both size and purchasing power. We are pleased to be able to add to the depth of our lines with the quality of Soft & Beautiful and Just for Me products.” This interview does not anticipate the massive shift away from chemical straighteners that occurred around 2009/2010. Armed only with advice from early YouTubers and limited products for kinky hair, many of us ditched our perms. Aimee Simon accurately describes the era when we shifted away from chemical relaxers, it “…birthed a generation of influencers who documented their natural hair journeys, transforming the industry, market, and lives.” Between 2012 and 2017, relaxer profits may have dropped by almost 40%. With the improvement of synthetic wigs and the accessibility of high-quality human hair wigs and weaves, many women stopped relaxing their hair altogether.

In the past few years, there has been a noticeable increase in Black women relaxing their hair again. On social media, women are documenting their return to relaxers both at home and in the beauty salon. Some are relaxing because they are returning to traditional sew-ins, which require leave-outs. Without a relaxer, they have to apply regular heat to the hair so that it will blend smoothly with a straight or wavy weave. As a result of consistent straightening the hair that has been left out becomes damaged and unhealthy. Some link this “return to perm” movement to the pandemic, where women sought out “ease” and familiarity in the scary and discomforting time. For others the answer is much simpler, they started relaxing again because they wanted to.

New scientific studies advise that using chemical relaxers is not a debate of ideology, but a matter of our health. Recent studies reveal that there may be a link between early and prolonged exposure to relaxers and decreased reproductive health. In 2022 The Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI) argued that there is a higher risk of uterine cancer in women who use certain hair products, including chemical relaxers. This study differs from earlier ones that identified higher rates of breast and ovarian cancer in women who used similar products.

The “to straighten or not to straighten” debates are as old as chemical relaxers themselves. In about a century, the product and its process have undergone many changes, many for the worse. In part two of this series, we will discuss the scientific developments relaxers have undergone, especially if the revelation about their danger is valid.

Thank you for reading. Be sure to subscribe to BlackBeautyPop so that you never miss an update.

While we often use the terms afro and natural interchangeably, the afro was a more structured style that was often achieved through the use of afro kits which may have relaxed the curl pattern. On the other hand, naturals refer to hair that was picked out without being structured or styled in any particular way.