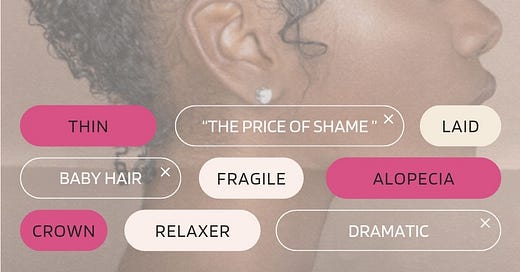

This full beat considers who benefits from Black women and girls' “edge” shame.

My interest in Black women’s beauty culture means that I also explore things that we, collectively, do not find beautiful.1 I grew up with thin edges and learned very early on that a lack of edges was decidedly not beautiful.

I wore bangs and swoops (fluffy and slicked), oiled my scalp with Wild Growth and Doo Grow, styled my faux locs and plaits to the side, talked to dermatologists and gynecologists, applied minoxidil, considered Rogaine, wore headbands and scarves, all in the name of concealing my shameful truth; I have really thin edges.

The first draft of this essay was titled, A Confession, and while I tend to lean towards the dramatic2 that was a total accident (or Freudian slip perhaps). I understand that this fact about my hair is not anything to confess or apologize for, but it did not always feel this way. Lately, I have been thinking a lot about the role of shame in beauty culture and whether my “edge” issues are emblematic of a larger issue. So, I turned to the outlets that most influenced my self-perception growing up to (1) trace our cultural distaste for thin edges, and (2) identify who may have benefited from the shame of not having edges.

In my search, I found very few articles, interviews, or op-eds about edges, specifically in magazines created for Black women, before the 2000s. I searched Black women’s lifestyle magazines that were available online, including Ebony, Essence, and Jet. I also looked through some of my print magazine archive, which includes Flair, Vibe Vixen, and Honey magazines. I found that excluding warnings against wearing braids too tight, there were only a few mentions of thinning edges (specifically related to medical issues).

2000 - 2010

By the 2000s, there was a notable increase in warnings against wearing tight weaves and braided hairstyles, lest they damage one's “crowning glory” (Ebony, 2001). These warnings often came in the form of celebrity hairstylist columns and interviews (Jet, 2006). Besides these recommendations from stylists, the only other focus on thin edges came from hair regrowth ads. These ads typically featured testimonials, photographic “evidence,” and a guarantee that the product could regrow hair. This limited dialogue suggested that thin or balding edges were likely caused by user error, such as putting too much tension on their hairline. While some hair loss may have been caused by an overwhelming amount of tension, there was little mention of possible medical or genetic conditions that may have also contributed to hair loss. For example, one of the earlier mentions of how conditions like “scalp psoriasis, dermatitis or other severe skin and scalp issues,” may cause hair thinning was published post-2010 (Ebony, 2012).3

The presence of these ads and interviews suggests that the approach to edges in the 2000s was one of extreme caution and blame. Stylists were lamenting about customers who were reckless with their fragile edges and corporations claimed to provide the “solution” to their restoration. Did corporations engender an “Edge Scare” for profit? According to Yael Wellisch “...a threat to consumer’s self-esteem, confidence or control often results in the desire to purchase a product that can restore what they believe is lacking. This phenomenon benefits beauty companies, which frequently present their products as solutions to women’s physical imperfections.” So, whether or not major corporations created concern about balding edges matters less than the fact they profited off women’s shame about not having them.

2010 - 2020s

Later, YouTube provided Black women a platform to engage directly with one another about our hair. Most of the videos about Black women and thinning edges fall into two categories, (1) concealment or (2) restoration. While ads and profit still impact which videos are prioritized, there is much less mediation between consumer and product. Social media allows consumers to leverage their influence to market products on behalf of brands and the comment sections elicit testimonials from satisfied followers/consumers. Comment sections allow creators and brands to gauge consumer interest in a given product, based on the intensity of communal mourning of the edges followers used to have or always dreamed of. In this case, the desire to hide or reverse edge loss also generated a profit for content creators and brands.

The conceal or restore edge pendulum persists on social media and I fear that it will remain emblazoned in Black women's psyche. Cathy O'Neil shared that shame conditions and traumatizes those whose bodies don't adhere to beauty industry norms, and this shame is used to build up a loyal consumer base. I wrote that many of us have developed a “compassionate approach to beauty standards,” but this does explain how corporations transform their messaging to appear as if they align with shifting cultural values.

As I noted elsewhere, thinking about Black Beauty Culture is complicated and often leaves us with more answers than questions. In this case, I am left wondering,

Why did corporations develop an interest in Black women’s edges in the 2000s?

Will there be an edge “revolution” where Black women and girls move beyond the restore/conceal binary?

If the binary remains, what technological developments might we anticipate in the edge department? For example, more realistic kinky lace edges or faster recovery time for hair transplant surgeries?

We and collectively are being used loosely here.

My big three are Pisces, Cancer, & Gemini, so I was destined for drama.

The cited issue only briefly mentions medical/genetic conditions as a possible cause of thin or balding edges and then immediately shifts to warning the reader of putting too much tension on her edges.